Building a Non-Native Mobile HTML5 App, Part V: Testing the App

23 October 2012

Posts in This Series

- Part I: A Business Case

- Why our client chose to build a Web app over a native one.

- Part II: Choosing a Technology Stack

- How we chose our tools and technologies, and what we picked.

- Part III: Hooking Things Together

- Wire up a client and server with JavaScript and .NET.

- Part IV: Making It Work Offline

- Store data locally and synchronize it with a server.

- Part V: Testing the App

- Develop and test for a mobile device.

- Part VI: Making It Look Native

- Leverage some tricks of Mobile Safari to make a site look like an app.

We’ve picked some technologies to help build our mobile HTML5 app, seen how to communicate between it and a server, and discussed how to store data offline for situations when a network connection is unavailable. In this post, we’ll take a look at how to ensure all of these components work the way they should: testing.

Local Testing

Most of the time, you’ll want to test your mobile app locally, on a fully-featured computer. This helps you quickly identify the most obvious layout issues and bugs, and requires no more than having access to the same computer on which you’re developing.

Since the app we built was designed to run on iOS devices, it was important our local testing included Safari, Apple’s Web browser. Though Safari is no longer available for Windows (an older version is still available for download), we’re fortunate to have access to Mac laptops, making Safari testing much easier. Though OS X’s version of Safari isn’t the same as that running on iOS devices, it’s close enough to catch most major layout and behavioral issues.

.NET developers, take note: the built-in Visual Studio Web server, commonly known as “Cassini”, doesn’t allow remote connections, a necessity when testing a site hosted on IIS from another computer (such as a Mac, for Safari testing). IIS Express, the new alternative to Cassini, allows remote connections with some configuration, but still has to be running to accept requests. Instead, we recommend always running sites in IIS. In addition to enabling remote connections, this also more closely matches what typical .NET production environments look like.

Device Testing

As soon as possible, you’ll want to add device testing to your routine, ideally with the specific devices on which your app is designed to run (for us, this included the iPad). Since we’re creating a Web app, not a native one, it’s considerably easier to “deploy” the app for testing to the device: simply visit a URL in the device’s Web browser.

From here, it’s quite easy to test for layout and style problems, as a simple visual inspection will reveal most issues. Debugging behavior, however, is a tad more difficult. Fortunately, Apple has provided some useful tools for figuring out what went wrong on mobile Web sites.

Prior to iOS 6, Mobile Safari provided a “Debug Console”, which displayed JavaScript errors encountered during the execution of a Web site. With the newest version of iOS, however, the Debug Console has been replaced with a brand-new remote Web inspector, which connects the iOS device’s browser to a desktop version of Safari, including all the great Web inspection tools it offers. Though iOS 6 was released after we completed our mobile Web app, this feature has since become a staple for all our mobile development work on Apple devices.

Network Testing

In addition to testing layout and behavior on mobile devices, it’s also crucial to test their network connection capabilities, as well. Though most developers seem to have access to high-speed networks (either 4G cellular connections like LTE, or just a regular wi-fi connection), many users are stuck with painfully-slow data transfer speeds. We’ve found the best way to test this is to simply take your mobile device out into the wild, and see what happens. You’ll encounter flaky cellular towers in rural areas, overloaded bandwidth downtown, and everything in-between.

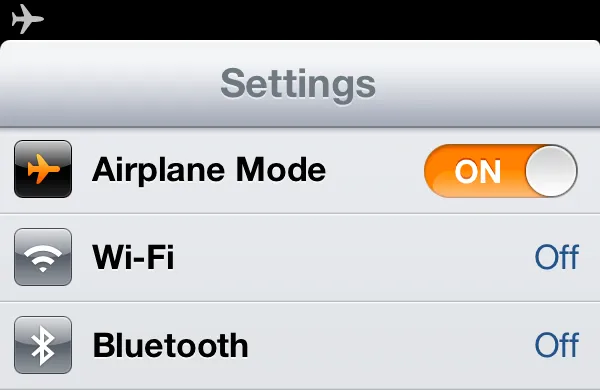

For apps that require offline support, as we discussed in the last post in this series, most mobile devices include an option for “Airplane Mode”, a way to placate those annoying demands to “turn off all mobile devices” by disabling all wireless activity, including wi-fi, Bluetooth, and cellular antennas. Fortunately, this feature works outside of airplanes and airports, as well, and allows us to test how apps will work without an Internet connection.

In this post, we’ve seen a few ways to test the various aspects of a mobile Web app: locally, with IIS and Safari, and on a device with some built-in iOS tools, and discussed some techniques for seeing how your app may behave in limited- or no-connectivity environments. Ultimately, it’s crucial to try out your Web app before it’s unleashed on your users, and I hope you’ve seen how easy this process can be. Next time, you’ll see some tricks to make a plain Web app look almost native. Stay tuned!